“My father broke his back while skydiving”

My instructor, understandably, paused. I had tried to say this as casually as I could, however, when asking me why I was skydiving today, she had probably been expecting an answer more along the lines of “I’ve always wanted to skydive” or “For the adrenaline rush”.

“I’m sorry” I added, filling the silence “that was probably a weird thing to say”. Of course, I had known this when I had said it, however, in a few minutes, I was going to be jumping out of a plane at 10,000 feet strapped to this person, so it felt weirdly prudent to be honest.

She made eye contact with me briefly and simply replied “OK then” as if she understood. She resumed adjusting my harness, as if nothing had been said, and pulled the straps a little tighter.

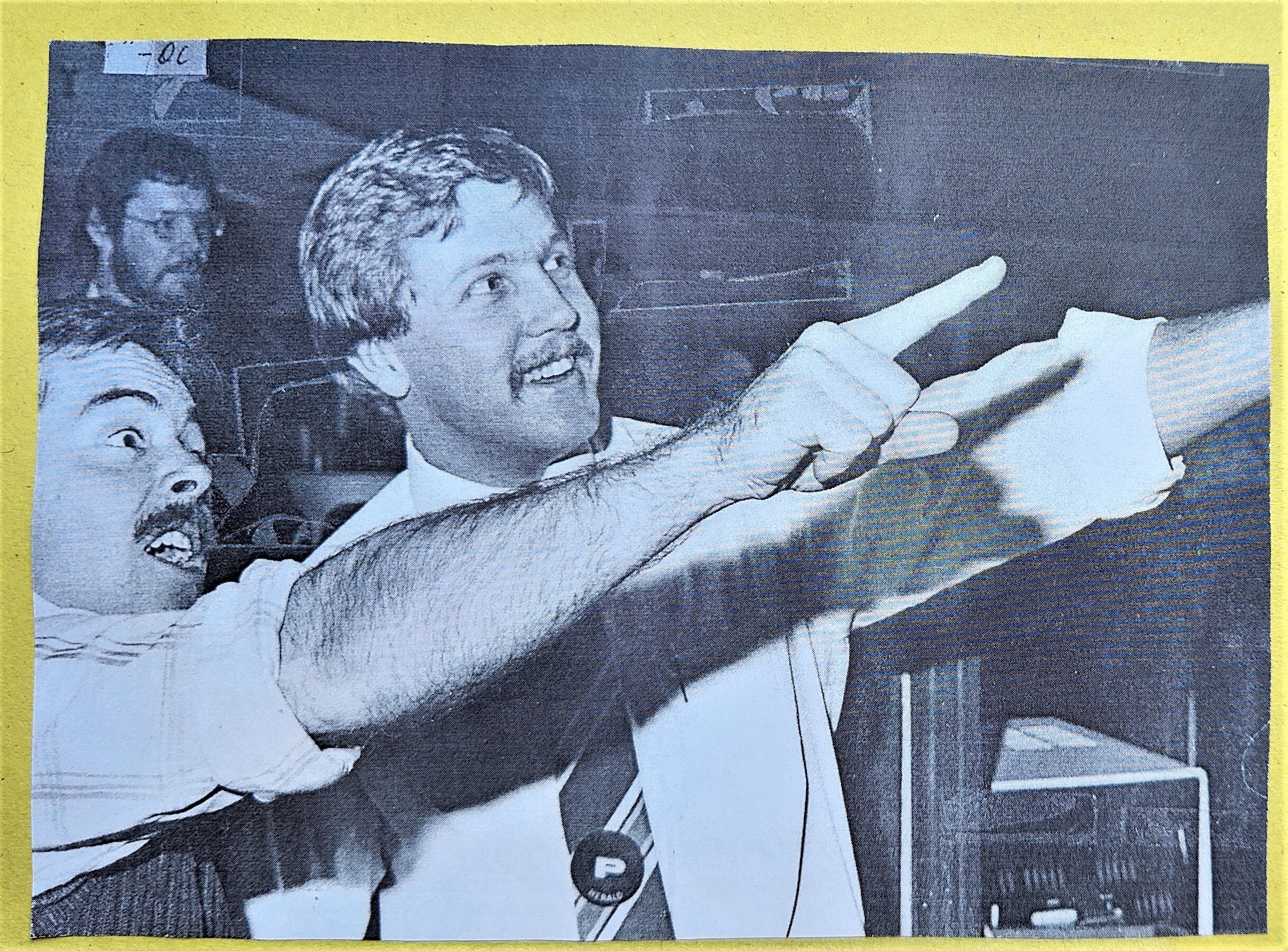

My father, in his early twenties

My father was 24 when it happened. He was living and working in Sydney Australia - the city he grew up in. Back in those days, safety precautions weren’t quite what they are now. Today, if you want to go skydiving and haven’t done it before, legally you need to first do a long training course before you can skydive solo, and often even a tandem jump (in most parts of the world anyway). For a tandem jump, you’re strapped to an instructor and you skydive together as one unit. The instructor (hopefully) deploys the parachute and controls the landing, you’re just the cargo.

My father didn’t have that luxury.

He was working for a radio station at the time. As part of a piece that was going to be broadcast across Sydney and beyond, he was to skydive - recording his experience the entire way through on audio. With a cassette recorder strapped in his shirt pocket, and deathly afraid of heights, my father jumped out of a plane alone, having never done it before. Most skydives today will be done from around 10,000 feet. His was done from around 2,500 feet - his parachute had to be deployed almost immediately. While his parachute deployed successfully, there was a windstorm, which meant that my father was blown miles off course from the intended landing spot.

With no real concept of how fast he was moving or how far off course he was, and trying to steer the cumbersome WWII-style parachute so that he wouldn’t land in the middle of a motorway (and hence be crushed by oncoming traffic), my father headed for an open field. He slammed into the ground in the middle of nowhere at a speed later estimated to be around 70kph. The point of impact was his tailbone.

It should be noted that prior to this moment, my father was certainly no stranger to pain. He had grown up playing rugby league, and had a long list of various injuries he had accrued while playing the brutal sport. He had broken bones and been in hospital many times before – it went with the territory.

When he hit the ground that day, the pain was unlike anything he had ever experienced before. The wind was knocked entirely out of him – this sensation he knew, but never so savagely. As he fought for breath, the waves of pain crashed over him. He described it as feeling like a steamroller was running back and forth over his body. He lay there sprawled on the ground, the pain was so intense that he wondered if he was going to die.

However, what was far worse than this was the terror he felt. As he regained his breathing and some composure, he realised he couldn’t move any of his limbs. He was, at that point, paralysed.

During the course of the two hours that he lay there in agony – unable to move, facing into a blistering Australian November sun – he thought of how he might end his life. He did not want to be paralysed. But as he couldn’t move he had little option but to lay there.

After a while and with intense and constant efforts, he slowly regained some movement in his right leg. Then his right hand and, eventually, arm. The pain was near unbearable, but he didn’t pass out. During this time, he talked the entire way through to his cassette recorder, which he had been carrying with him throughout the jump. He talked through the pain, his fears of what might become of him, how he would try to end it if he was paralysed. When breath allowed, he calmly spoke aloud all of his thoughts, taking some comfort in the fact that they would be recorded and heard if he did not make it.

X-rays later revealed that he had crushed and fractured two vertebrae. One of the fractures stopped perilously close to his spinal column. Two weeks later in hospital the doctors discovered he had also burst his stomach open, along with other less significant damage to much of his body.

Said photos, and the instructor notes post-jump

Eventually, an instructor and the friends he was jumping with found my father in the field. There was no stretcher, no ambulance, and little sympathy. My father’s friend took out his camera and took some photos – he thought it was rather funny seeing my dad smashed up and wanted to capture the moment. They assumed he was being a wuss. My father – possibly delirious with pain, sunstroke, and frustration – told them to help him up. He grabbed hold of one with his right hand and threw his arm around him. The other picked up his limp left arm. Hopping on his right leg between the two still-amused helpers, my father staggered back to the van which the group had arrived in. It was about one kilometre away. He had to climb two fences to get back to the motorway. When he got inside, however, he found he really could no longer move. The pain had reached such a level that he was now certain he was soon going to die. He says he remembers the pattern stitched across the seat fabric, wondering if this would be his last thought.

My father in hospital

Soon enough he got taken to the hospital, where the extent of his back injury was discovered. He was then taken to another hospital that was better able to care for him. In the days ahead, he slowly regained movement. It would be two weeks before his stomach injury was discovered when he was violently ill in the middle of the night and, unable to roll over because of his back injury, it was feared he would drown in his own vomit. Surgery the next day repaired his stomach. When he finally got on his feet, he was put in a large brace, from neck to hip to ensure that he was unable to move in such a way that would potentially exacerbate the damage to his spine as a part of his recovery. He wore the brace for four months.

Oh, and the recording? The mic cable was dislodged on impact. You could hear my father chat lightly as he floated to the ground, then crash….and static. Nothing was recorded beyond that moment.

My father considers himself exceptionally lucky. Indeed, he says he is blessed, as if the vertebra had split a couple more millimetres and he may never have walked again. And despite everything that occurred, he walked again, ran again, played sport again, had kids – most would never have known the accident had happened. While two of his vertebrae were crushed, the fracture healed and his spinal cord received no permanent damage. He did, for years, live with exceptional, chronic pain as a result of the injuries, and suffered endless nightmares from the incident. But, as of the time of writing, he is one of the healthiest, strongest people I know.

The parachute school where he jumped was closed six months later. Four people died in the weeks after my father’s accident, and the school was alleged to have been using parachutes which were rejected as inferior by other parties.

All in all, it could have been much, much worse.

I heard this story growing up in dribs and drabs, from as early as I could understand such things. I cannot recall a time that I was not aware that my father experienced back pain. The earliest explanation consisted of five simple words “I broke my back skydiving” to eventually, as I got older, the more detailed story you have just been told.

But even the five word version of this story given to me in my young adolescence was enough to make myself deathly curious about skydiving. It had harmed my father - my invincible, all-powerful father.

So naturally, one day I’d have to try it.

Doubtless influenced by that story, I was acutely terrified of heights growing up. At playgrounds with climbing frames and jungle gyms, I would rarely, unless exceptionally coaxed, climb to the top. I even had issues going down large slides due to the loss of control associated with descent. Many times at water parks or theme parks my fears got the better of me when I reached the front of the queue for some particular attraction. I would have to head back down the way I came, walking with my head bowed past the long line of other kids, all eagerly waiting their turn.

One of the more morbidly embarrassing moments I can recall was when I was 14. During a school trip to a PGL centre, a group of us were put through a kind of ‘high rope’ assault course. This consisted of a few obstacles from climbing over tall logs, walking tightropes, and ending with a ‘leap of faith’ style jump from one upright log to another - all with a safety harness, of course.

Climbing up the upright log on the leap of faith, logistically, was straightforward enough. The handholds were generous - there may as well have been a ladder attached to it. It wasn’t incredibly high up either - it can’t have been more than 10 feet tall. Most of my peers climbed it with ease, largely without hesitation. Most made the jump to the other log too, and even those that didn’t were fine because of the aforementioned harness.

I was one of the last to go. To add to my embarrassment, a girl who I had a huge crush on was in the group, watching. I had just about managed to get through all the previous obstacles without holding everyone up. But this was on another level. It must have taken me five minutes alone just to pull myself over the top of the first log. When I finally got up, clutching to the harness as tightly as I’ve clutched anything, I stared at the gap I was supposed to leap across and froze.

For what was probably a good twenty minutes, I remained there, paralysed with fear, going through states of sobbing, to resolving myself to jump, and breaking down again, saturated in self-loathing and cowardice.

I remember the instructor, an encouraging young man doing his best, cheering me on.

I remember seeing the blurred outlines of my classmates through teary eyes.

And I remember finally giving up completely, and climbing back down the way I came.

I didn’t make the jump. That stuck with me.

As I got older, I managed to claim back a bit of self-respect when it came to heights. The first time I went indoor rock climbing I froze after climbing a mere four feet, and demanded to be let down - to the great dismay of one of my good friends who was partnered with me. Eventually however I was able to somewhat consistently reach the top of various walls, with a certain amount of encouragement. I learned to push down the fear and take things one step at a time.

Occasionally, as we all do, I would come across sweaty-palm-inducing videos of adrenaline junkies doing skydives or freerunning, and wonder what it would be like to be able to do that. Or sometimes I would watch videos of Yves Rossy - the self-labelled ‘Jetman’ who had a dream to one day fly like a bird, so he built his own personal jet-powered set of wings to do so. And they worked. The way in which he controlled his flight was primarily through arching and collapsing his posture - altering the wind’s flow around him, changing his direction. Many people have dreamed of human flight, Yves Rossy is perhaps the only human to have truly experienced it.

There are few people I’m jealous of in this life, but Yves Rossy is one of them. He can fly.

Yves Rossy

But the videos that really shook me were videos of base jumpers - people who would jump off a high cliff or building, deploy their parachute after a few seconds of free fall, and then (hopefully) land safely. I say hopefully because, perhaps more morbidly, I would also compellingly watch videos whereby the jumps went wrong. Videos where the parachute opened at odd angles, throwing the jumpers into cliffs, or ones whereby the wingsuits caused the jumper to spin uncontrollably. I thought of my father. What it must have felt like.

Base jumpers know the risks, and yet, they do it anyway. The idea of just having the self control to walk off a cliff and jump, knowing these risks, and perhaps survive and laugh it off, was - and still is - barely fathomable to me. To stare death in the face as you fall, to catch the wind and, if it works out, land unscathed. It seemed to me to be, in a way, the height of self-mastery.

When I was 24, I resolved to go skydiving for my 25th birthday. I had been in a dark place in my life for some time, and I felt like I needed to do something to shake me out of it. I wanted to feel something other than simply hollow, and lacking any interest in life.

I had heard an anecdote from someone at a party that their experience of skydiving made them fear for their life, and reminded them that they actually wanted to remain alive i.e. this was a very positive experience for them, perhaps even a profound one.

I wanted that.

As I looked into booking a dive, it was impossible to escape the parallels with my father - trying to do the same thing at the same age he did. In a way, my motivation was mainly fuelled by spite. My attitude towards myself was such that I was ashamed of the place I had got to in my mental and emotional health, and so doing a jump felt like a dare to the universe - do your worst, I don’t care.

It’s easy to think of yourself as not superstitious, up until the moment when you have to confirm that yes, you really are signing up for skydiving. Statistically, tandem skydiving is safer than driving – you’re more likely to be killed on the way to the airfield, than from the activities performed there. As much as I liked to think of myself as a rational man, I hesitated.

After some thought, I decided to try and make it into an actual birthday celebration instead of some sadistic solipsistic existential test, so I invited some of my closest friends - most of whom have known me since I was 11. These are my ride-or-die guys, the people I’d trust with anything.

However, hilariously, one by one they all undramatically declined the invitation. Citing reasons from the understandable I’m not sure I’d like that to my mum wouldn’t like it.

Skydiving = possible death

Upsetting certain parents = certain death.

Granted, I did not properly articulate the gravity to which, personally, this whole ordeal had to me – but mainly because that seemed like a dick move. “If you’re really my friend you’ll jump out of this plane with me” reeks of a certain degree of manipulation. So I simply resolved to go solo.

When hearing that my friends weren’t joining me, my father offered to join instead.

I know. I was mortified and impressed beyond belief that he would even consider it. It was such a him thing to do. It gave me considerable pause - roping my dumbass friends into this was one thing, but my father? After all he’d been through, I wasn’t sure it was such a good idea. He hadn’t ever tried to skydive again after his accident, understandably. So by joining, he’d be doing it for me, not himself. We chatted about it over the course of a week or two, but we couldn’t pin down a date that worked for either of us, so eventually just let the idea drop for the time being. I was relieved.

If I was going to do it, I would have to do it alone.

I planned to do it the following year, but then the pandemic hit. After an airfield opened up again for skydiving, I booked to go skydiving by myself.

Driving to the airfield, I found I was surprisingly calm, despite having been a nervous wreck for the week prior.

I accepted that whatever was going to happen, was going to happen.

I ran over my father’s story in my head over and over again as I approached, and tried to make peace with it. I really tried to imagine what I’d do if the same thing happened to me or worse. What would be left outstanding, what regrets would I have?

As the uncharacteristically sunny hills of England rushed by, I realised I was fairly at peace. Sure, I’d have some regrets, some things left unsaid, some scores not settled and so on. But on the whole, I would have lived a life I was grateful for. Easy to say when you’re uninjured perhaps, but compared to where I had been years prior, it was a wonderful realisation.

After I arrived and registered, myself and the other jumpers were put through what you expect - safety briefings, short drills and so on. Some of the other people jumping that day included a man who had been given the experience as a gift from his wife. He facetimed her and his two-year-old daughter as we were waiting. Alongside us, there was a small family jumping too, all of whom seemed quite unsure why they were there in the first place. Normal people, having a bit of fun.

My tandem partner was cool as hell - she exuded an easy, serious competence. She told me she had been skydiving for ten years, and taught the military parachute squad as part of her work. She was due to do nine tandem skydives that day, I was merely the first.

Doubtless influenced by her calm demeanour, I found I really wasn’t that nervous. In fact, to my great surprise, I was hardly nervous at all. I expected to be close to panic as I got on the plane, but as we took our seats I realised that I’ve been more nervous on certain dates. Though perhaps that says something about my romantic inclinations, I digress.

As we ascended in the small rickety plane, I learned that most of the clouds sit at around 1,000 feet, and as we soared through them into the otherwise clear open sky, I was told that any skydive from 5,000 feet or above basically looks the same, apparently.

At 10,000 feet, it was time to go. I had been attached to my instructor, and we wiggled our way out to the open hatch. The air was cold, rushing, the only sound. One by one, some of the more experienced solo jumpers on the plane leapt out. Perhaps it’s odd to say, but it occurred to me I had never - at least, in person -simply seen a bunch of people just fall before, one after another. Moments later, my instructor counted down, and we fell out too.

I could offer up some description of what the freefall felt like, or the subsequent parachute ride to the end - but I can’t really offer anything that you probably haven’t heard before. It’s exhilarating, possessing an incredible intensity and simultaneously having a somewhat dreamlike quality. But what really stuck with me, perhaps as a guy who grew up in grey London, was the sheer infinite blue of the sky as you dive out of the plane. Above the clouds, you swim in it. Hanging in the air after the parachute deployed, I tried to drink it all in. I want to go back.

The serenity of the experience was only disrupted for a single moment. As we glided down through the clouds, suddenly I could comprehend - and imagine - falling from the height we were at. 10,000 feet is too much for my brain, but apparently 1,000 feet is comprehensible. A familiar jolt of fear caused me to hold my harness a bit tighter. A few lines of fabric separated me from freefall. The brutality of physics. I found myself simply repeating “wow” and “thank you”.

We drifted down in graceful swoops and arcs. She was a pro, and landed us smoothly, precisely, and without drama.

For the rest of the week, I was as relaxed as I can ever recall being. Suddenly my mental map of the world was expanded - I was down on ground level, but I had been up. The world was bigger. My problems, literally smaller. What could phase me now? I had just jumped out of a freaking plane, and was fine. My father was also, understandably relieved.

And as I write this now, a few months after the fact, I carry that jump with me still. It’s stuck with me.

There’s a quote from Euripides, the ancient Greek playwright, which goes “The gods visit the sins of the fathers upon the children.” There’s a similar line in the bible and in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

Had my father not hurt his back while skydiving, and had it not been for my fear, I’m not sure I would have been as motivated to do it. We inherit more than we think, and probably more than we’d care to admit, from our parents. I’d be hesitant to say that we’re obligated to deal with the obstacles our parents left for us, as I think you can do with your life as you please. But in a sense, perhaps we have no choice. And though there was no basis for this thought, I had this strange sensation that if I didn’t tackle this fear, someone else would have to. Like it would be passed on, somehow, in some way.

After we landed and decoupled, I thanked my tandem partner once more. She laughed it off, and said that she needed to go straight back into the plane to do another tandem with the next group. While this may have been a cathartic, emotionally significant experience for me, this was commonplace for her, her day job. I was just the first shift.

As she headed off to the next group, she turned as she walked and said to me with a smile “Is your back ok?”

I laughed and said “yeah, yeah it’s all good”.